The Seed Beneath the Volcano

Vol. I, K. Rajasekhara ReddiPantulu had a special prayer room on the first floor of his house, exclusively for himself. Others should not enter the room. Photographs of great people of the Theosophical Society were there, in that room and there, portraits of Mourya, Maitreya, Jesus and Koot Hoomi had a special place. A photograph of Annie Besant, in meditation, dressed in a pure white dress, and sitting on the skin of a tiger, was prominent among them. Pantulu used to meditate, daily, in that room for one hour. After he enters the room, the house remains completely calm till he comes out—that was a routine item for all in the house, every day.

One day, while Pantulu was in his prayer room on the first floor, a child in the ground floor began to cry continuously. The mother could not control her. Everyone was upset and afraid. As anticipated, Pantulu rushed out of his prayer room ferociously and slashed at the child, in the mother's arms, ruthlessly. He shouted, 'Get the hell out of the house! All riff-raff gathered here and ruined my meditation. All my vows are violated. How awful!' So shouting, he rushed out. Like a whirlwind.

Anybody should get ablated in his wrath. The infant's body was immediately inflamed and writhed in great pain. It was a shocking sight for Krishna, who watched silently. Never before had he seen him like that; nor did he believe that he could act in such an inhuman manner. A shudder ripped through him. He felt as though he was beaten. He was unable to see the misery of the crying child unabatedly.

The strokes on the body of the child were a question mark for him. From childhood days, everybody preaches in the society, 'Anger is your enemy, calmness is your protector. Children are different forms of God,' etc. Many more such statements are being dinned, again and again. They all appeared like question marks for Krishna.

'Is this the same grandfather whom he considered an embodiment of high values? Is this the same person renowned as a great meditator? It is said that meditation ushers peace. Is this that peace? It is said that meditation gives bliss. Is this a bliss? By meditation, concentration is supposed to be increased. Is this the effect of concentration? By meditation, complete control is said to be attained. But complete control is lost by meditation?' he questioned.

All of a sudden, Krishna developed disregard, light heartedness and despise for his grandfather. Pantulu had decended to the level of a hunter and a butcher—a cruel and inhuman act. Krishna took it to heart and became deeply depressed.

His nascent, crystal-like mind began to think differently. His sole aim of life itself changed into a question mark. That powerful question mark was going to play a very important role in his quest for Truth in the future. It was going to be the foundation or basis for his search and research for Truth.

Krishna was known for his lavishness among his circles. He did not care for money. He never knew what frugality meant. He never hesitated to spend. Any amount of money could be spent easily by him. If money was not given as much as demanded, there would be so much shouting that his demand had to be honoured, under any circumstances. He was obstinate by nature if he was not satisfied. His grandmother would be the target for his demand. She used to think, 'Next time, not a pie will be given to him.' But if he would ask for money again, she would readily comply, though she did not know why.

Suddenly, the cupboard of his grandfather attracted his attention. That is all! The amount was spent, whenever he wanted, as he liked.

In the name of school fees and other requirements, he was taking money and he was remitting it in the school, as fees, in the names of poor students. He was providing books and other stationery also. One day Pantulu questioned the propriety of his expenditure. 'If money is earned by hard work, then, only, its value will be realized. I am struggling hard to earn money and you are spending it away in no time. There should be some limit and control for your expenditure—you understand?'

Krishna felt unhappy with the remarks of his grandfather. He was angry. 'Am I spending your money? What are you doing with the income of my mother's property? You may treat my expenditure as from my mother's money.'

Pantulu was shocked with this reply. 'Oh! You have the cheek to ask me accounts of your mother's income? All right! Are these thoughts your own or is anybody poisoning you? To spend for anybody and everybody in the town, you don't have heaps of your mother's money, Mr. Krishna Murthy,' Pantulu pungently retorted, looking at his grandson with apparent anger.

Pantulu wanted to control the expenditure of Krishna. He locked his cupboard and the keys were kept secretly. However, he was giving him necessary money for his daily expenditure. The money was not at all sufficient for Krishna. Without spending money, there was an itch, tickling his fingertips. He was hissing like a cobra. Immediately, he opened his grandfather's cupboard with some other key. The cupboard opened itself very easily. Krishna became a master in opening his grandfather's cupboard whenever he liked to take money—as much as he wanted.

Pantulu observed that money was missing from his cupboard, which was locked by him, securely. How was the money disappearing? One day Pantulu observed his grandson opening the cupboard. The grandfather was angry and questioned him, 'Taking away money like this without permission is theft. Theft is a crime. Do you know that?'

Krishna cooly replied, 'If you give me as much as required, why do I resort to theft? There is no other alternative!'

'Wonderful! Since I did not meet with your lavish expenditure, you committed theft and are justifying it! In my family, there had been no criminals. I can't understand from where you imported this habit. Some time back people hoped that a young man like you would become a great man in the future, in the course of time.'

Krishna didn't pay any heed to his grandfather's remarks. Pantulu was tired of him and gave away the keys to Krishna, sarcastically saying, 'You take away the keys and spend as you like! Will you kindly at least note the actual amount you have taken on a paper and keep it in the cupboard? The cash balance is not tallying, who knows how much the clerk, also, is taking away?' Without any hesitation, Krishna took the keys from his grandfather.

* * *

In 1916, the construction of the building for the Theosophical Society at Gudivada Center was completed. Pantulu named it 'Krishna Nivas' and handed it over to the Society. On the other side of the building, there were some rooms and they were let out to shops, like a Shoe Mart and Book Depot. The rent was utilized for maintenance of the building. The clerk of Pantulu was collecting the rents.

Sometimes they were paying only half the rent, saying that the other half was taken away by Krishna. Pantulu was getting angry and was unable to guess what his grandson was doing with all of the amount.

Once Pantulu obtained the bills of Krishna from the stationery shop. Three dictionaries were purchased! Any sensible student would buy one dictionary!

Pantulu asked Krishna why he bought three dictionaries. Krishna calmly replied, 'One for me. The other two for my friends!'

'Oh! Then you can, as well, provide dictionaries to an entire class. What do you lose?'

'I have no objection.'

Pantulu was unable to decide how to bring him round.

Next month, it was the turn of the shoe shop to send a bill for four pairs of shoes. Pantulu turned to the clerk and ordered him to ask the shopkeepers not to give anything, either in cash, or in kind, to his grandson.

Subsequently, there was a short payment of rent. Pantulu asked the clerk for the reason. He submitted, 'Sir, as directed by you, I asked them not to pay the rent to Krishna. Accordingly, when they refused to give him money, it seems that he had threatened them.' He added, 'They are afraid of him, and they were unable to turn him back empty handed.'

For a minute Pantulu was silent. He said, 'Let him come home. I shall thrash out the issue today.' He turned to his wife, who was standing at the door, and said, 'Have you not spoiled him? You have been very lenient towards him, and so he is wagging his tail as he likes. Tell him that I have to cut it! Control the fellow!'

Durgamma expressed her helplessness. 'Oh! My God! How to control him? He does not care even a twopence for me. He heckles me. If I advise him, he frowns at me and threatens that he would quit the house, once and for all. No. No! I am helpless!'

After some time Krishna came home happily. His grandparents were silent on seeing him. Perhaps Pantulu's heart melted, like a little lump of butter, on seeing the innocent child. But he pretended to be angry with him and said, 'We have been fulfilling your childish desires, as you like. Still, your expenditure has been always on the increase; there should be some limit and control for it. Have I earned for the sake of everybody in the town? Are you threatening the tenants? What do you mean? Are you the superhero of the town?' Krishna paid a deaf ear, totally, like an ascetic. Pantulu again continued, 'Can you ever know the value of money? If Dhanalaxmi is not given due, she won't stay, beware! I am unable to understand your nature. I don't know how your life will be in the future! You give a instantaneous rebuff if I advise you about anything. I don't know how to get along with you.'

* * *

In the month of Aswin, every year, Dasara Festivals are celebrated. When Bharatamma was alive, the festivals were organized on a grand scale. For nine days, the 'Court of Dolls' was kept arranged in a glorious manner. For her, it was a sacred Yagna. All the dolls that had been collected from her childhood had a place in the court. Most of them were idols of Sri Krishna, in different colors and sizes. They were made of clay.

In some houses, at the center of all the dolls, a pitcher and an idol of Goddess were arranged. Bharatamma used to place a large idol of Sri Krishna, also, at the center. Friends and neighbours were invited to receive fruits, turmeric, vermilion, betel leaf and a nut set. With the death of Bharatamma at the house, celebrations were stopped.

Dasara days usher in those memories for Durgamma. During those festival days, she used to distribute annual tips to all the servants, employees and others. Krishna was active in his own way during the festivals.

One year, during Dasara festivals, a new idea flashed in his young mind. Immediately, he procured the keys of the iron chest of his grandfather and opened it. There were small handbags containing gold coins in the iron safe.

He quickly brought them, and came out, going towards the bazaar. Some poor street people were moving hither and thither. He called them by waving his hand. They promptly assembled in front of him. He distributed gold coins one by one. In disbelief, their eyes were protruding. Unbelievable! Are they dreaming? Is it an illusion? No, they are real gold coins glittering in the sunshine. They thanked him, bowed their heads, and ran away as fast as they could.

Pantulu came to know of it. He was startled, aghast, for a few movements his senses were paralyzed and fossilized; he was unable to digest it.

Durgamma was petrified to the roots of her being, afraid how her husband would react. It is a kind of careful investment accumulated over a period of time. In a jiffy—all gone!

Time froze. Deep silence pervaded in the room. Krishna stood like a Buddha statue in the pagoda, devoid of feelings. His face was like a sphinx in the Egyptian desert, touched by nothing, moved by nothing.

For Pantulu, the very thought of it was maddening. Many images, scenes and promises, rolled in his mind's eye. He waded out from the sea of his reminiscence and slowly gained his composure.

He said in a quite voice, devoid of anger, 'Kittu, are you fully sober or is your mind off balance, utterly? Are you fully aware of what you are doing? When you were spending lavishly, we reconciled ourselves, that you were childish and innocent.' He stopped a while, wiped off the sweat from his face with a towel and continued 'but today, like a simpleton, or a stupid who does not know the value of the gold, you committed theft and distributed the coins like shells to all of the passersby. Are they free pebbles on the seashore to give away as you like?

'How can I understand your erratic acts?' Pantulu was unable to decide what to do or what to say. He kept mum, gazing at his grandson, for some time. Krishna sat still, staring blankly like a mute.

He added, 'Why have I been struggling to earn money? It is for you and you only, for our future happiness. The gold is intended for you, to lay golden roads for you. If you earn and save money then, only, you can understand my agony for what you did today. We have been dancing and singing at your command, for your pleasure. We pampered you and learnt a bitter lesson,' he said.

Krishna continued to be silent and indifferent. Pantulu got irritated and again said, 'What happened to you and your mental balance? There is sense in alms-giving in a humble manner. But you stole the gold coins and gave them away as alms. If you begin to empty the iron chest every year like this for alms-giving—well, are you thinking that you are emperor Sri Harsha's incarnation? Why don't you speak out your heart? Like the status of Buddha, why do you keep standing silently? Whom have you consulted? Tell me the fact!' He paused.

As though he had just returned from some other realm of life, he slowly opened his mouth and replied, 'You don't give if I ask for them. So I stole them. I don't know why I wanted to distribute them to poor children. I just gave them away. That's all.'

Pantulu did not keep quiet. He again commented, 'Great, for treating gold and brass alike, you should be either a Maha Yogi or a dunce who does not know values. I don't know how to manage with you or how to understand you or how to bring you round.' So saying, Pantulu pressed his head with both his hands. Everything was confusing for him. Durgamma continued to be a mere spectator for the tussle between the grandfather and grandson.

Once again, Pantulu wanted to make him realize his anguish. 'People give alms when asked for. Without being asked for, you are giving away gold coins as you like. You are not Sri Krishna to give boons to poor people like Kuchela without being prayed for. Tomorrow, if anybody asks you for the shirt you are wearing, will you give it away?'

Krishna was totally indifferent. He did not feel even a pinch of his words. Had he repented for what he did, probably Pantulu would have eased himself.

Krishna replied, 'Why only my shirt? If asked for, I will give away my knickers, also, and come home naked.' Pantulu was stunned and silent. How to bring round this stubborn fellow! That was an unanswerable question before him.

The whole scene disturbed the mental peace of Durgamma totally. She remembered the behaviour of her own daughter, Bharatamma. On Sankranthi festival once, the mother of Krishna gave away a silk saree to a trained bull player. When Durgamrna asked her, 'Why have you given a silk saree, while so many old sarees are there in the house?'

Then Bharatamma replied, 'I wanted to give it, I gave it. At the time of alms-giving, will anybody consider all those things?' Durgamma recalled the words of Bharatamma. She, too, was giving away anything and everything whether asked for or not. He was born and his mother died. He is a living legacy of her. The devotion and philosophical attitude were inherited from her.

* * *

In the fields around Gudivada, Pantulu was growing pulses and paddy. The fields were given out for lease. There was a written agreement between him and the lessee as to how much the lessee has to pay him every year. Pantulu was afraid that the lessee may not abide by an oral agreement.

His lessees were not rich and they lived by hard labour. One day a lessee by the name of Bhushayya came to the house of Pantulu and waited to see him.

After finishing the daily prayers and breakfast, Pantulu sent word for Bhushayya to come in. Pantulu was sitting in an easy chair in a relaxed mood. Bhushayya put out the cigar, hid it, entered the room of Pantulu and bowed to him in a humble manner. Pantulu enquired, 'How are the crops, Bhushayya? Are the thrashings over? Why have you not remitted your lease amount so far?' Thus questioning, Pantulu began to turn over the newspaper's pages.

'Yes, Sir, I have come to submit,' murmered Bhushayya, scratching his head. Pantulu was silent. Again, Bhushayya hesitatingly said, 'Sir.'

Pantulu asked him, 'Having come all the way, why do you hesitate to speak out?'

Bhushayya spoke out in a humble tone. 'Sir, this year the yield is low. The pests have toiled the crop. Not even one-fourth yield is realized.' So saying, Bhushayya kept quiet, looking at the facial expressions of Pantulu. Pantulu appeared indifferent and he was turning the pages of the newspaper.

After a few minutes he asked, 'What have you said? The yield is less. There were pests. Is it my fault? Sorry, but what can I do?' Bhushayya shuddered at the question.

'Sir, if you are pleased to question like that, what can I say? To whom can we narrate our grievances expect yourself? Kindly, be kind. I am not in a position to remit the lease amount. Be merciful.'

Pantulu peeped out of the newspaper and said, 'There is no place for my kindness here. As per the agreement, the said amount should be remitted to me. Am I right?' He looked into the paper again.

'Yes! This year, due to the problem of pests, we have not even received our investment. Sir, I can't remit to you the amount as per our agreement, only you can save me! For every rupee, I can't give more that 25 paise; beyond that, we can't even expect to have our daily food grains. What can I tell you about our situation? It's the worst.' Bhushayya spoke out of his heart.

Pantulu remained silent for a moment. After some time, he kept the paper on the stool and said, 'As you are pleading so much, having regard for you, I will give you a little consideration, but giving 25 paisa for one rupee cannot be agreed to. Agreement means agreement. This is the agreement. Is it not?'

'Yes, we live by squeezing the soil. Who will consider our difficulties except yourself? I have none else to depend upon,' submitted Bhushayya.

Pantulu nodded his head. 'Bhushayya! Earlier, whenever the yield was high, I never asked you for even one rupee more than the lease amount. You paid as per the lease only. I considered it as your luck. Is it not?'

'Yes, Sir! Your are magnanimous. You have been generous to the poor,' agreed Bhushayya.

'Then? Since there is loss this year, is it fair to ask me to bear the loss? You, yourself, tell me. When you had profits, I was happy. Now, you are facing loss, I am sorry. What else can I do?' questioned Pantulu.

Bhushayya again submitted, 'Sir! You are righteous people. All these years, we have been living under your mercy and support. I performed my daughter's marriage also. This year I am very unfortunate. God is not kind to me. Kindly be merciful and show me a way [out of this hardship].'

'How is it possible, Bhushayya? You know if an agreement is violated, it is a crime,' said Pantulu, raising a law point.

'Yes sir! I am not contradicting what you said. I am not retorting to you. My only submission is that you may consider my condition sympathetically,' appealed Bhushayya.

Earlier, in the case of another lessee, Pantulu had to drag him to court and seized his properties. As such, his lessees had been afraid of him.

After a little while, Pantulu replied, 'Bhushayya, I am not denying your statement. It is your bad luck. With sympathy for you, only, I already told you that I will give you a little consideration at the time of payment. But I don't agree to receive 25 paise for a rupee. Even if I agree, the Law does not agree. All of us should abide by the Law. You cannot escape from these troubles. So you find out a way for yourself. Think well.' Thus, Pantulu threatened him by making a reference to the law.

Bhushayya continued to plead, 'It is impossible for me to pay more than 25 paise for if I have to remit more, we will have to starve for food or sell away our house, without a shelter for us. Kindly come to our rescue and give us food, we gratefully think of you day in and day out.'

'Listen to me Bhushayya! Why so many words? I abide by the agreement. The whole town knows that. Since you are telling me that there is a loss for you, in consideration I will give you duration at the time of payment. I have nothing more to say. I have some other work to attend to.' So saying, Pantulu got up from the chair.

It was not clear how much Bhushayya offered to remit, and how much consideration Pantulu was ready to give. 'Your mercy sir, I am not fortunate. I shall reconcile with my bad luck,' said Bhushayya in desperation. He looked like a dried-up and dangling crop.

In the next room, Krishna was reading a devotional book and, incidentally, he followed the conversation between grandfather and Bhushayya. Through the window, he looked at Bhushayya also. Krishna experienced a type of anguish and he was sad. He observed Bhushayya leaving the house slowly with a bent head, looking at the ground. Krishna could not underrstand why grandpa behaved so unkindly. Why was he not sympathetic towards Bhushayya? Why this inhuman overlordship? A deep sadness came over him. He felt a while a pang of guilt. Is it angst? Kindred spirit? An ingrained sense of empathy?

Contrary to this incident, Krishna recalled another incident which took place earlier, about a destitute old woman who came to their house praying for shelter.

On the eastern street of Gudivada, there lived a Brahmin priest with his wife and three children. Long back, they migrated from Bezwada to Gudivada and settled there. After some time, the priest died and the sons began to live separately with their families. By turns they looked after their mother for some time. Gradually the daughters-in-law began to dislike their mother-in-law and she was finally sent out. The old woman began to roam about in Gudivada at the mercy of the public.

A Muslim Shaheb recognzied her and recalled her earlier, happy days. He pitied her and provided shelter for her in his house. He knew her traditional life, and, as such, he made it possible for her to live independently, preparing her own food. After some time, the gentleman was shifting to Guntur and he took her to her son's to leave her there.

Her children did not allow her to come into their house, declaring her an outcaste and she had lived under the shelter of a non-Aryan. Shaheb accompanied her door to door. No Brahmin family came forward to give shelter to the 90-year-old woman. Suddenly, she remembered Pantulu and asked Saheb to take her to Tummalapalli Pantulu, with a hope that she might get shelter there.

With the help of a walking stick, the old woman came to the house of Pantulu carrying a little bundle of her clothes under her shoulder. She sat on the pail and sent in a word for Pantulu. In a few minutes, he came out but could not recognize her.

With half-opened eyes, the old woman looked at him and said, 'Can't you recognize? I am Kamakshamma, wife of the priest at Bezwada. All of us were staying in the same area. Your first wife was brought up in our house. This is my present plight. After the respected priest passed away, I was not wanted by anybody. I am destitute.'

Pantulu recognized her and asked, 'Why have you come here like this? What happened to your sons? You look miserable.'

'All that is my bad luck. I am not wanted by my own children. There is nobody to see my end. On the advice of my daughters-in-law, my sons have deserted me. God in the form of a Muslim sahib came to my rescue for some time. There is some indebtedness between me and this man. Today he is going away. I moved from door to door and I was turned out. By God's grace, I remembered you. Will you allow this old fellow to come in? Eating the remains at your house, I shall spend my time in a corner of a room,' narrated the old woman.

The old glory of the woman was recalled by Pantulu in detail. In those days, she was like goddess 'Laxmi' and as an elderly housewife, she was liked by everybody in their area. Pantulu asked Muslim Saheb to leave her with him and take leave.

Pantulu told her, 'Please come in.' She responded, 'I was doubting whether you, also, would drive me out or receive me kindly. God is great. You are kind.'

'Take a bath and have proper food. So many people are eating with us. You won't be an additional burden for us,' Pantulu said. After six months, she passed away calmly, while asleep. Pantulu sent word for her sons and necessary funeral rites were performed under his supervision.

On that day, Pantulu very kindly received the old woman and came to her rescue. But today, the same grandfather sent away Bhushayya, disregarding his pleas. Why did he behave like this? Krishna could not understand.

After a few days, a person came for Pantulu, sweating all over the body. Pantulu was out of station. He approached the clerk and told him that he came to clear a debt. Some time back he had taken a loan of 500 Rupees. Later, his whereabouts were not known. Notice was issued in his name. But he did not turn up. Now, suddenly, he appeared with money in hand. The clerk picked up the promissory note and calculated the interest in his own way and finalized the net dues from the borrower. On hearing the figure, that person was swooned, 'So much! How can I pay it? I did not know the compounding process of interest, and that I have to pay heavily now,' he explained, himself.

The clerk calmly replied, 'Listen! Kankayya! This is the order of Pantulu himself. If violated, I will lose my job. Repayment should not be accepted, even if it is short by one Rupee. What can I do? After he returns from Madras, you may appeal to him. In my opinion, his order was final. He won't revise it.'

'Oh, God! Already I have been facing loss after loss. I have taken a loan, mortgaged my house, and I am clearing different debts here and there. Yours is the remaining large debt. Will you kindly plead with Pantulu, on my behalf, for mercy, sir?' Kanakayya requested the clerk for a sympathetic word in his favour.

Kanakayya was a cloth merchant. He purchases at a wholesale rate and tours villages carrying the bundle, selling the clothes door to door. Once, while he was sleeping in a choultry, keeping the bundle under his head, it was stolen. By the time he returned home empty-handed, his wife was bed-ridden. He could not make both ends meet. He mortgaged his house to clear his debts, including the dues to Pantulu.

The clerk spoke to him in a soothing tone. 'Kanakayya, difficulties will not last long. Poverty and wealth are like the two pots, hanging on either side of the shoulder yoke. Don't you know that? So, I will show you a way out of the present crisis.' Kanakayya was eager to know this solution.

'Now, you remit the money you have brought with you. You execute a fresh promissory note for the balance due from you. If you delay more, the money on hand today, it may not be there tomorrow. The growth of interest is faster than the speed of a horse.'

There is some such saying, and that is true always. One more word, even if you prostrate before Pantulu and pray for mercy, he will never yield. He is very obstinate in such matters; he will never yield. Come on! How much have you now with you? Let me finalize your transaction!'

The clerk was wordly wise. If once Kanakayya leaves the room, no one can say when the money comes back again. It is said that money is thousand-legged. It may go in any direction. So it is always a wise step, to collect the money at hand, without delay. A bird in the hand is always worth two in the bush.

Kanakayya had no other way to go than to follow the advice of the clerk. A fresh pro-note was executed accordingly. He left the room, comparing himself to a baldpate man facing a hail storm.

Krishna observed the incident and wondered at his grandfather's money-lending business. He sympathized with Kanakayya. He could not understand why his grandfather was squeezing money from needy people like that, unsympathetically. He wondered whether it was the same grandfather who was very charitable elsewhere, and who was secretly helping poor students? What is this duality?

Two contradicting behaviour patterns of the same person—how is it possible? Why is he appearing differently at the same time? Any lacuna anywhere?

Till then, Krishna had a great regard for his grandfather. Of late, Krishna began to think of removing the mask of his grandfather, so that he could understand his real, internal nature.

Krishna had been observing such individuals, with dual personalities, all around him. He had observed double-tongued persons also. He was perplexed to understand the realities.

* * *

One day, Krishna laying on his cot, closed his eyes tightly. There was pitch darkness. When he pressed his eyeballs, covering them with one hand, he could see a streak of light all over the mental horizon. Some shadows appeared in different colors, such as azure, light green, golden brown, sometimes light yellow and reddish. Shades turned into visible figures and images. Smoke-like columns passed like rings. These images appeared while mixing with one another and vanished. From the fast disappearing image, all of sudden, somewhere, a penetrating ray of light passed through the mental sky, like a flying arrow. They were not static but shadows of colors, continuously fleeing. When he covered his forehead with his palm, everything vanished in no time. It is a different sky world, dense of darkness; after a while some fleeing light appeared.

* * *

All these activities in the mental horizon, he observed carefully, minutely, intently and interestingly. He thought to himself 'It is a wonderful game,' so it became his hobby.

Govinda Rao was one of the occasional visitors and on that day; he was chatting with Pantulu in a leisurely way. 'You, alone, could subdue the arrogance of that Englishman. Others could not. He is a very haughty Rogue,' commented Govinda Rao, referring to the incident.

An Englishman was residing in Gudivada. He was discourteous. He used to take photographs of ladies, whenever and wherever he wanted. Local people objected to it but he did not care for them. Finally, they complained to Pantulu. Pantulu felt indignant and warned him severely. He sent a message to the Englishman, 'Give respect and take respect, if not, you will be dragged to court. Be aware.' The Englishman heard of Pantulu and his reputation. He also knew the association of Pantulu with the Theosophical Society. He was afraid of Pantulu, and, afterwards, began to behave properly.

Coffee was served to Govinda Rao and Pantulu. After sipping the coffee, Govind Rao commented, 'Our people first murmered against the new custom you have introduced. Now, everybody is adapting it. Recently, in the marriage at our relative's house, we also observed it.'

'Yes, I am told of it. I could not attend the marriage. My wife told me that everything went on well there,' said Pantulu, wiping his mouth with a towel. Till then, there was a custom in Brahmin families to personally invite while extending invitation cards. The personal invitiations were extended twice. Unless invited three times, the invitees would not attend the marriage. Pantulu did not like that. He said, 'A personal invitation along with the invitation card is sufficient.' He implemented what he said and his associates also followed him. Gradually, citing Pantulu, all others followed the new custom.

Krishna suddenly entered the room and Govinda Rao enquired about his education. He also asked about his learning of new Sanskrit Verses. Krishna smiled at him and replied, 'very many, Uncle' and went in.

Govinda Rao keenly observed Krishna and he felt very happy. He remarked, 'Pantulu, please don't think that I am praising your grandson. What I feel in my heart, I am telling you. If he is observed carefully, it can be seen that he has characteristics of a great man. His grace and dignity are unique. He is majestic in gait like a king. I feel that he will be the top person in some field or the other. Just a crown is missing.'

Pantulu did not feel flattered, when Govinda Rao spoke highly of his grandson. He remarked sarcastically, 'He does not need a crown for himself. Every day he is already putting a crown on every one of us,' remembering all the pranks of Krishna.

'No, no, you should not say that. It is only childishness; I understand why you are pungent about his behaviour. He distributed gold coins to poor children as he liked without your knowledge recently. Is it not the reason for your remark? From his childhood, I have been observing him closely. I do not know the actual field in which he flourishes. But I can dare say that his name and fame will spread all over the world in the future. It may not be as you wish it to be. The present situation is a temporary phase; when he grows up, he will teach hundreds of people,' said Govinda Rao.

'I don't know; sometimes, I feel disturbed about him as to how to bring him up. He has hardly any regard for elders. He is not humble by nature. He does not bow to anybody nor does he listen to anybody. He acts as he likes. He does not hesitate to give away anything and everything. If questioned, he gets irritated and behaves rashly. Added to all this, he is adamant. Setting all these characteristics aside, if his educational achievements are considered, there is nothing but cipher. I am unable to understand his attitude and behaviour. The trend of his life is unpredictable. How can a plant which could not be bent in its early stages, be bent after growing as a big tree?' commented Pantulu.

'Pantulu! Please don't get agitated or worried. As time passes on, everything gets right. At present, your grandson appears like a burning coal underneath white ash; when once the ash is blown off, the brightness of the coal is seen. He will definitely flourish in his life. By the way, you, too, might have heard that the great poet, Rabindranath Tagore was very irregular at school. He did not follow the lessons occasionally, he was appearing as if he descended from a heavenly domain. But, he was awarded a Nobel Prize to the surprise of everybody. You know all these things very well. One day your grandson, also, may excel all others in the world,' said Govinda Rao.

* * *

Every year Pantulu was performing the annual ceremony of his daughter, Bharatamma, on a large scale. That year, there was a specialty for the ceremony. The father of Krishna was attending the ceremony. Krishna and Sitaramayya would be meeting one another for the first time, after many years.

'Aunty! It seems Sitaramayya is coming over here for the ceremony. After so many years, perhaps, he had a desire to see his son. Naturally he would be happy to meet his grown-up son,' commented a visitor with Durgamma.

Durgamma replied, 'Great! His affection has been overflowing all these days, perhaps,' sarcastically.

'Krishna, it seems your father is coming over here,' that lady said looking at Krishna who was passing through that room at that moment. Krishna did not give any reply.

The visit of Sitaramayya was discussed by everybody as they liked.

'Who is this father about whom all these people are talking? What does he look like?' The boy tried to imagine his father, but he could not. The same thing happened in the case of his mother, also.

On that day, as expected, Sitaramayya arrived at the house of his father-in-law. Pantulu introduced him to Krishna saying, 'Krishna, He is your father.'

'Father! After so many years, I am seeing you. What happened to you all these years? Why did you not come to see me even once?' Such ideas and questions did not spring up in the heart of Krishna.

As though it was a casual meeting, Krishna looked at him and thought, 'This man is my father, as they say.'

Pantulu said, 'Why is it, you are standing there only? You go to him and sit with him.'

'This is the first time for the boy to see his father. He is hesitating to approach him. Naturally, he shirks,' said somebody.

Sitaramayya looked at his son with wide-open eyes. The boy looked as if made of gold. He was very charming. He felt inexplicable happiness on seeing him. His affectionate heart began to throb.

Pantulu repeated, 'Kittu! Go to you father and sit with him.'

Krishna approached his father and the father received him affectionately and made him sit on his lap. Touching his head tenderly, he asked, 'Krishna, how are you? Studying well? It seems that you can recite Sanskrit verses very well,' said Sitaramayya. The boy nodded his head and replied slowly, 'I am alright.' After a few moments, Sitaramayya asked him to go and play as he liked. Krishna jumped out like a bird which was just set free.

From the moment Krishna saw his father, a number of questions and doubts began to rise up in his mind.

'How can I know that he is my father? Everybody is saying in one voice that he is my father. So has he become my father?'

Krishna was observing butterflies flying hither and thither. He continued to observed them steadily.

Again in his mind, a number of questions sprouted like paddy. 'A stranger was brought before me and I was told that he is my father. If he is not introduced, how can I know him as my father? How is it possible?'

It is not a frivolousness or a puerile of a child. It is a question which sprang up from his inner heart in its own way, a question which had a peculiar angle of apperception. 'How can I know, myself, that he is my father?' He began to try to answer it himself again and again.

So somebody should introduce a new thing for the first time. If it is not thus introduced, whatever that thing may be, it cannot be recognized. That is to say, if identity is not given, identifying capacity is wanted.

'How can I know him as my father?' For this question, Krishna wanted a logical answer. Doubting everything, questioning everything, are two of his important mental activities, which would help his surroundings. A keen sense of observation, and ability to investigate, require a doubt, or a question, as the first step.

'How can I know himself as my father?' He pondered on and on. No tangible answer came out. A full stop—still. The question winds itself inside of him and entwined him in its deep folds.

Revolutionary questions would not emanate from the philosophers and other fountainheads of intellectuals, but they were in the very existence of mankind. The entire knowledge of all the generations of human race questioned? The processes like questing, dissecting, critically observing, analyzing and synthesizing are very important steps in investigation and research. These mental activities of Krishna were considered as far above his chronological age.

Arangements for the annual ceremony of Bharatamma, on the next day, were already made. A number of guests, also, were expected to attend the lunch.

From early hours on the ceremony day, everybody was busy. The scheduled items were being cooked on a special furnace in the yard. Black gram cakes and rice cakes were being prepared on a large scale, keeping all the invitees also in view. Nobody paid any attention to Krishna and his morning requirements. He was angry. He quarreled with his grandmother. She tried to pacify him. But his irritation did not subside. He was looking this way and that way to find out an outlet for his wrath.

Suddenly, the fried black gram cakes in a large plate received his attention. He began to pick them up and tore them into pieces, one by one. He turned to the nearby basket and began to tear the rice cakes also, as he liked. The pieces were thrown all over the floor. If anybody came in his way, he was retorting, 'Who are you to interfere? It is my own will and pleasure.'

Suddenly Pantulu came there in an angry mood. Already something went wrong somewhere. Krishna did not pay any attention to his grandfather. Pantulu shouted at Krishna, 'You kinky fellow! What are you doing? What is the matter with you?' But Krishna was deaf to him. He continued to tear and throw down the cake pieces as he liked.

Pantulu could not control his anger and he lost his temper. He removed his waist belt and slashed his grandson twice with it. 'Your misbehaviour is becoming more and more intolerable. You have neither respect nor fear for anybody. I tried to bring you round in all possible ways. For everything, there is a limit. We are pampering you pompously; you are ill treating us!' he roared.

At that moment, none could anticipate what would happen. The onlookers could not believe their eyes and they were shocked at the turn of events. In a fraction of a second, the belt was in the hand of Krishna. He was ferocious. Biting his teeth, he retorted vehemently, 'Who are you to beat me? Who empowered you to slash me? Simply because I am a child, do you want to harm me inhumanly! What do you know about me? Be careful!' Thus warning Pantulu, Krishna repaid the slashes with interest on the back of Pantulu ruthlessly. His revolt caused tremors of terror all around. His eyes were red and respiration was fast. He was totally revengeful at that moment.

It appeared as though, in place of the boy, Krishna, there was an elderly person who was taking vengeance on Pantulu. Some such sprit appeared to have taken possession of Krishna at that time.

Pantulu was standing breathless and aghast. He never dreamt of such a revolt from his grandson. With blank looks and a silenced mouth, Pantulu stood staring at Krishna.

Everyone around had been afraid of Pantulu. None could dare to face him or attack him till that minute. Before so many people, he was beaten black and blue, by his own grandson, with a leather belt. Everyone expected Pantulu to react violently, losing all sense of decency and sobriety. Anything might happen, they were fearing.

But nothing happened, Pantulu did not react at all, as anticipated. Krishna had been a child in his arms and bedside. The revolt of Krishna caused more dismay and inexplicable surprise in Pantulu. He was moved at heart, tumultuously in silence. He became completely calm and reflective in his attitude towards the boy immediately.

He did not treat this act as an indication of arrogance of Krishna. All that happened represented an 'action and reaction' process for him. The incident was a clear indication of budding self-respect, personal independence and a strong desire for freedom in Krishna, he analyzed.

After Pantulu left that room, Durgamma asked Krishna, 'Are you right in beating your grandfather? Is it not wrong, Ramudu?'

'Then is it right for him to beat me? In what way is he superior?' he questioned her back. He did not think that his grandfather spared him. He looked around as if he was warning everybody, 'If I am meddled with, I will not keep quiet. I don't care for anybody.

'He is the head of the family. From your infancy, your grandfather looked after you with utmost care. Can you ill treat him like that even if he had beaten you, in an angry mood, do you think that he does not love you, and has no affection for you? Is it fair not to respect your grandfather? Should you not bow to him?' asked Durgamma, feeling much for the insult which her husband had swallowed silently.

'I will not keep quiet if I am beaten. No one has a right to lay hand on me. If I am insulted, I will not spare anybody. If I am beaten once, I will beat ten times. Do you know who I am? Let him be God, I don't care. That's all!' Not a trace of repentance in Krishna. He would never allow anybody to boss over him nor would he be submissive to anybody in life. Perhaps this incident was an illustration for his sense of his values.

Afterwards, Pantulu did not beat him again. He remembered his promise to his daughter on her death-bed.

* * *

Pantulu asked him, again and again, to pay attention to his education. He arranged tuitions also. But Krishna did not evince any interest. He continued with indifference. Education of his grandson continued to be a major problem for Pantulu.

'He won't read at Gudivada. He may go astray beyond recovery. To put him in the groove, I feel change of the surroundings is better. I wish to admit him at Hindu High School, Machilipatnam. What is your opinion?' consulted Pantulu.

'That is a good idea. His attitude may change at Machiliptnam. Without further delay. Kindly send him to Machilipatnam,' replied Durgamma.

Till then, their grandson had been with them and they felt for his separation, a little pang. But the future of their grandson was more important.

Krishna was admitted at Machilipatnam in Third Form. He was asked to stay with Saraswathamma, the elder daughter of Pantulu, in Frenchpet. When Vemuri Chinnayya Rao was staying at Godugupet, Krishna was born and lost his mother.

It is against the nature of Krishna to stay on at a particular place like a 'frog in a well.' He always liked to travel from place to place among new people, as he had wheels on his legs and wanted to be free and have freedom.

Krishna was vexed with his school, its furniture and teachers, feeling uneasy to continue there. At that moment, he welcomed, happily, to go to Machilipatnam.

It was a new place with a new school and new friends. He adjusted himself immediately to the new surroundings. Everything was well. Children of rich cultivators, such as Mandali and Chalasani, were his close friends. He began to move about with them freely and spend lavishly. He was in the habit of spending; he was second to none. His interest in this school also started to abate within a few days.

When he came across new words, he was, necessarily, consulting a dictionary. When once he learned a new word, he never forgot it. He was learning different grammatical structures in English gradually. Thus he improved his English day by day.

While at Gudivada, his grandfather was observing and supervising him and his movements. But at Machilipatnam, he was free from such observation. Whatever he wanted to do, he could do immediately as he liked. At the house of Chinnayya Rao, everybody treated him tenderly, remembering him as a motherless child. Narasimha Rao, the eldest son of Chinnayya Rao, was two years younger than Krishna. As such, both of them moved closely and very affectionately about as natural brothers.

At Gudivada, Krishna had a separate prayer room. But at Machilipatnam, though there was no such special room for prayer, in his own way, he was continuing it. When he began to meditate, sitting in Padmasana Posture, he would lose sense of time totally. One day at lunchtime, people waited for Krishna impatiently and searched for him. He was sitting in the corner of a room upstairs in mediation. They were surprised at his deep concentration at such a young age.

Krishna was good in imitation and mimicry. He was imitating different artists and entertaining everybody, every day, in a new way.

* * *

In the olden days the rich Brahmin families had a strange hobby and a custom known as 'doll's marriage.' This function was performed by them, like an actual marriage, with all the paraphernalia, and was followed by a sumptuous lunch or dinner.

But the supposed 'elders' of the marriage party were chosen from young boys and girls below eight or nine years of age. Boys would wear shirt dhoti and upper cloth over shoulders, girls wore blouses, skirts and saree pieces.

The bride and bridegroom would be decorated in rich clothes. They would also have gold covered ornaments, which Machilipatnam had been very famous for, for generations.

In those days child marriages were in the vogue. They strongly believed that by performing in these marriages, their children would be married soon, by a suitable match. However it was a purely children's function all the way with fun, frolic, mirth and merriment. The whole atmosphere was festive.

The Vadlamannati and Vemuri families were relatives residing in houses opposite each other at Machilipatnam. One day both families decided to perform a 'doll's marriage' on a big note at Vemuri. Chinnayya Rao's house. They duly invited relatives and friends.

The boys and girls were selected and allotted to them certain roles to play chairs were placed opposite directions and all boys and girls seated.

Krishna had a major role to play as father of the bridegroom. He wore a new shirt, dhoti and upper cloth. He sauntered here and there and raised his voice to show his assumed authority as a bridegroom father. There were mock arrangements and counter arguments over some imaginary faults with the marriage arrangements.

Krishna, as usual, dominated the proceedings by displaying many antics of his choice. Everybody thoroughly enjoyed the gaiety and had a gala time.

One day, on return from school, Krishna observed everybody dull and serious, as if they had lost something valuable. Aunt was sitting in a corner in a melancholic mood. Children were searching for something. Keeping books on the table, he asked, 'Aunty, what happened? What are they searching for?'

She replied,'My ring is lost. It is not found anywhere. No outsider stepped into the house. All the efforts to trace it have failed.'

'Where did the ring go? It might have slipped somewhere in the house. Probably, you did not search for it properly. It may be beneath the almirah or behind the rice bag,' said Krishna.

Krishna asked her not to be dejected like that. 'The ring did not disappear Aunty! It should be somewhere, here only. I am sure of that. Slowly and carefully search for it again. You will find it,' he said confidently.

She smiled at him and said, 'If it so happens as you said, you will have a Machilipatnam sweet.' All the children again searched for the ring.

'Mother! The ring is found,' brother Krishna said.

'It is lurking behind the bag,' shouted Narasimha Rao, handing over the ring to his mother.

Saraswatamma felt very happy. All her tension and anxiety disappeared immediately. Looking at Krishna affectionately, she said, 'How I wish that you should live for a full 100 years! Your word did not go waste. Is your word so powerful? We are tired and vexed and, in a minute, it is found after your arrival.' So saying, Saraswathamma distributed sweets to him and other children. Krishna was very happy.

The next day, Chinnayya Rao was going to Madras. But he could not return from the court in time. The train starts at Machilipatnam for Madras, via Bezawada. Saraswathamma was afraid he wouldn't be home early enough to go and catch the train. Already it was time for the train to start and he was still at home. 'I tried my best to leave the court early, but I could not. I am sure that I may miss the train.' So murmuring, he hastily packed up and dashed to the railway station followed by a servant.

Krishna observed the anxiety of Saraswatamma and told her calmly, 'Aunty! Don't worry, the train starts late today. By this time, Uncle may be seated comfortably in the train.'

'How can you say that, child?' asked Saraswatamma, ignoring his assurance.

Krihsna replied, 'It should,' calmly.

Within a few minutes, the servant returned home and informed them that the train started half an hour late and Chinnayya Rao would have plenty of time.

Saraswatamma was surprised and looked at Krishna with delight. 'How is it that whatever you say is happening? You are not an ordinary kid, you have some 'Vaksiddhi' (word power of a strong nature).'

Krishna was not much interested in playing with other children. But whenever he played, he was the winner. If the children divided themselves into teams, every child wanted to be on Krishna's team. Children naturally liked to be on the winning team. Even in the losing game, Krishna was always the winner.

Krishna was scoring minimum marks in the quarterly and half-yearly examinations. He was scoring the highest in English and lowest in math. Final examinations were fast approaching. He was reading the books for reading's sake and he was often absent-minded. Sometimes, he was not responsive. He used to respond as through he just returned from some other realm of life, all of a sudden.

He was not bothered about the daily happenings around him. It felt that there was an invisible line of separation between himself and others. He had his own internal world. He had his own thirst for something which none else had. This was his state of being, to chant the Sivamantra, unaccountably, within his innards.

Every year, the final examination question papers for the third form were printed, taking all the necessary precautions. But children were somehow procuring the question paper earlier. So the management adapted the stencils system. Only the necessary number of copies of question papers were roneod and the master copy was brunt away immediately. This confidential work was entrusted to one person by the name of Subba Rao. By this system, the question papers were secure and beyond the reach of pupils.

That year, the children wanted to procure the question papers somehow or the other. They discussed the issue among themselves. Krishna had immense self-confidence to make impossible things possible, and he considered the issue as a challenge for him.

Since the children resolved to procure the question papers that year, Krishna suggested an expedient idea for it. Accordingly, rich children of Mandali and Chalasani families collected 100 rupees under the guidance of Krishna. Early in the morning, Krishna and others met Subba Rao and told him what they wanted. He was afraid and refused to comply with them. Then he was tempted with the money and he yielded.

'Children! This is an extremely secret matter. Except yourselves, none else should know it. Otherwise, I have to face dismissal.' Everybody nodded, expressing consent. Keeping them outside, Subba Rao entered in, and with the original stencils, and he roneod copies of question papers. The papers were rolled in a newspaper and given to the children, with the caution to maintain the secrecy, once again.

As soon as they received the question papers, they felt that they had achieved something great and they were extremely jubilant. Krishna said, 'These are not for our use only, they should be useful for everybody. All our classmates must be benefited. What do you say?' For some time there was disgreement and discussion. Finally, all of them agreed with Krishna.

Krishna had the habit of selfless motives. In the evening, by the side of the bungalow of Challapalli Raja, Krishna stood near a water tap at the crossroads and began to distribute the question papers to the students, as if they were chewing peas. At the time of distribution of these question papers, Krishna enjoyed immense happiness without considering the pros and cons.

Everybody came to know of the scandal in no time and the school authorities took Subba Rao to task. Though he tried to bluff for some time, when he was warned of police action, he had to reveal the truth to the authorities. He was further questioned to mention the names of the children involved in the affair. Though he hesitated to mention the names for a few minutes, he told the fact that Krishna Murthy was the gang leader. The management dropped the idea of a police case, but he was dismissed.

Immediately the management got new question papers prepared for the examination. Further, they decided to debar these students from the school. Sri Chinnayya Rao, the Uncle of Krishna, was an important member of the managing committee of the school. He pleaded in the committee meeting that the children might be pardoned as it was a childish act and it was the first offence. Similarly, other members also condoned the offence of all those children.

Krishna and his friends, however, attended the examination formally and they could not answer anything. Krishna was, as usual, indifferent to his failure in the class.

On hearing that Subba Rao was dismissed, Krishna assembled all of his friends and collected another 100 rupees for him. They advised him to seek a job elsewhere.

Pantulu came to know of Krishna's behaviour at Machilipatnam and the malpractice. He had thought that a change of place would set right the boy, but he did not change. Pantulu felt very unhappy over it. 'God knows when he'll get stabilized and when he'll begin to live normally!' said Pantulu to his wife.

Durgamma tried to protect their grandson, saying that some mischievous children involved this innocent boy in their mischief, 'You don't come forward to support him like this. Our fellow might have definitely dragged everybody and instigated them. Don't underestimate him. We may have to face more troubles due to him in the future.' Krishna had to go back to Gudivada School again.

Pantulu patiently tried to convince Krishna to read well. 'My dear Kittu I am not able to understand why you are lagging behind in your school. I know that you have a tremendous memory power. Why are you not concentrating it on class work? Your mind is jumping up, this way and that, like a grasshopper in a school. Please control it and attentively follow the lessons. All my worry is about your future and your future life.' Krishna was silent for some time. He replied, 'Alright! Grandpa.'

Krishna did not know why he was unable to concentrate his mind on studies. Whenever he'd open up a book, his thoughts would behave like a locust—his mind would float and fly away. Perhaps, it was not within his control. The education of Krishna was like an iron piece before a magnet, which was losing its power. Somehow, he was pulling on in the school, class after class, as if he was dragging a carcass of an elephant. He did not pass any class for the first time.

* * *

For so many days, Durgamma was thinking of asking her grandson an important point. But she was forgetting it. So, one day she made a knot on the hem of her saree as a remembrancer. As soon as Krishna returned from school, the knot happened to touch her hand and immediately she asked him, 'Ramudu, for a long time I have been thinking of asking you one thing. It seems you'll go to a particular hotel, daily, and eat as you like. What is that tasty item there? There is neither cleanliness nor hygienic condition there. If you eat anywhere like that, will not your health be upset?'

Nimmagadda Ramayya was running a coffee Hotel at Gudivada. From 6 A.M to 9 P.M., it was very busy with customers. 'Pesarattu' was a specialty of the hotel. Adding pieces of ginger, onion and chilies, it was roasted with original ghee. Along with the roasted cake, a little coconut chutney was also separately served. Everybody in the town liked it very much; it was provided @10 ps. only.

Krishna was very much fond of it. Whether hungry or not, if he happened to go that way, at any hour of the day, he would enter in for it—not alone, but along with his friends, without fail.

Krishna replied, 'What have you been thinking about the most tasty green gram cake at that hotel? None on the earth can prepare it like that. It is simply a heavenly preparation. So, I go there for it!'

Durgamma smiled. 'Alright. But why such a long train of followers with you to eat at your cost?'

Krishna replied, 'Is it sufficient if I fill up my belly? My friends, too, like it very much. But unfortunately they don't have money. So I am paying for them. It gives me a great satisfaction. By the way, why do you make all sorts of enquiries about me like this? It is my will and pleasure.' Durgamma kept quiet for fear of a more pungent reply from him.

His intense quest for enquiry began at a very early age, surprisingly blossoming imaginative faculties like the aurora of the rising sun.

He was endowed with an open mind, questioning everything and anything. His attitude and expression had a direct impact on established social customs, rituals in the society, which he felt decadent and degenerative. He wondered why people followed blatently like slaves, without questioning.

He started questioning, himself, why people are unequal in their endowment—some are blessesed huge properties to enable them to enjoy at the expense of others, while the poor and downtrodden had to slog and slave for their livelihood throughout their life.

The authoritative, hierarchical structure pierced his sensitive, fragile mind and he felt pain and anguish about this enslavement, and inhuman treatment in the society. He did not understand, or fathom, why such abominal, detestable customs exist in the society. It is so unfortunate the people reconcile to their fate, as they could do nothing to transform their lives.

His grandfather's house servants had to slog from dawn to late in the night, unmindful of abuses and wild treatment. They got conditioned to this system for sheer survival. Though servants were always at his disposal he dispensed of all these ministrations and depended on self-help. In other words, he regarded human slavery as an anathema and did everything himself, without the help of servants, as he was endowed with a good physique.

Despite the hard work by the servants, his grandmother was always ready to shower abuses on them. They would continue to work, unmindfull of the nagging and abuses.

Durgamma had the habit of preparing the food fresh, serving hot preparations, always made from high-quality, costly ingredients. Curries were fried in pure ghee and the meals always ended with the serving of thick, creamy curd. Thus a very hot, sumptuous, very tasty meal used to be served to the whole family first and all the leftovers that remained were given to the servants.

Having witnessed this tragic, inhuman culture of treatment of loyal and hardworking servants, one day he insisted to sit with them to eat the same food given to the servants. Durgamma shouted at him, 'Ramudu! You are not supposed to eat with them. It is a taboo. Your pride birth in a high Brahmin family, would it not prompt you not to eat with them?' she said angrily. After a pause, she continued, 'They are our servants! How can you eat with them? It is most idiotic and abhorant,' and warned him of the grave consequences when his grandfather comes to know of this misdeed.

A servant boy, daily, used to sit on the veranda in the scorching heat of the summer, and would draw a fan made of vatti roots with a rope attached to it. Pantulu would have his siesta and enjoy the cool freeze provided by the fan. One day, Krishna sat beside him and was about to take the rope to do the job but the servant-boy objected vehemently. 'No! Little master. It is not your job. Go away. If master knows it, he would beat me to a pulp.'

However, Krishna forcefully took the rope and started moving. After a few minutes, his hand developed shooting pain. Krishna asked him how he doesn't have any pain while moving there. The servant boy nodded his head across, negatively, and said, 'I am accustomed to it.'

Despite many servants under his beck and call, Krishna would wash his clothes, clean pooja articles and sweep his room all by himself. Durgamma repeatedly told him not to do such petty things: 'That is unbecoming of you.' He never cared about her admonitions but continued to do so. One day she was annoyed by his stubborn behaviour, and shouted at him by quoting a Telugu proverb: 'It is as though the chief raised and reared a dog as big as a horse to protect his house. When burglars entered, the chief, himself, barked.' So to say, we procured these services by paying sufficient money to attend our daily chores. Their duty is to serve us. If not, why would we pay? Hence, why do you work? Leave it to servants.'

Krishna used to observe servants at other relatives' houses, he was appalled for their wantan, cruelty inflicted partisan behaviour by their masters, in spite of their immense labour, every day. Why are they reeling under penury? Why do they depend on charity? What made them to be so impoverished? Who is responsible for pushing them into this line of life?

He never treated servants with unkindness, he was very sympathetic and soft. He would donate his brand new clothes to the servants' children, to the utter dismay of Durgamma. Now and then he used to offer a small amount.

In the servants' lodging, there are no cots, no beds, only tattered old mats or bags to sleep on. Such disparities were very touching and made a deep impression on him. He never relented to this inhuman treatment of servants.

One day Krishna sought the answer to know why they are poor and inferior from his grandmother.

Durgamma said, 'It is their fate; they were born like that because of their misdeeds. They have to be content with what fate destines,' she concluded wryly.

What is fate? Who decides? He asked himself.

It is not as infantile, puerile and frivolous, as Durgamma thinks. She is not aware of the universal truth behind the probing.

Krishna's nascent mind was loaded with several pregnant questions and riddles, as if he was born only to question everything and anything! Or does the questioning quality become an inherent quality with him, to be his inborn, unique trait?

His fundamental questions raised by him had a deep meaning, a universality, an egalitarian outlook, nearer to ultimate truth. He, himself, a boy of his age, was not aware of the complications and implications embedded in it.

Is a 'prodigy of destiny' endowed with a pertinent way of questioning, to know that which lies, or hides, behind the real truth?

* * *

The prayer room of Pantulu in the first floor was under lock and key. No one was allowed to go there or peep into that room. When Pantulu was out of station, also, it was not opened, and the key was always with him.

Krishna had a longing to know about the secrecy of the room. He thoroughly searched for the key in every nook and corner of the house. His determination to open it increased more and more. He was thinking of it. Durgamma was strictly following the instructions of Pantulu, not to allow anybody even to go near the prayer room, in Pantulu's absence. But Krishna was waiting for an opportunity to open it.

Once, Pantulu had to go to Bezwada on court work. Durgamma went out to a relative's house. Krishna thought that it was an appropriate time for him to find out the secret. He had a bunch of keys with him always. He told others that he was going out and pretended to go out. But he went to the first floor by wooden steps surreptitiously. He closed the door near the staircase.

He thought that he might have to try all the keys to open it. But to his own great surprise, with the very first key, he opened the lock. He looked around to be sure that none were observing him, and slowly opened the prayer room. He felt it with a sense of guilt, as if he were opening a door which should remain closed. After entering the room, he closed it. He slowly stepped forward as if he was proceeding towards the destination for which he had been groping for.

He could feel an unknown fragrance in the room. He had a sacred feeling of entering a great temple. Krishna examined that entire room carefully. In this prayer room, he did not find pictures of Hindu Gods as in the prayer room of the ground floor. He observed the photographs of great people related to the Theosophical Society in this room.

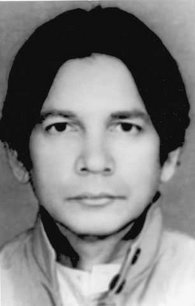

Why did his grandfather prohibit others from entering this room? What speciality might be there in those great people? He recognized one of the photographs as that of Annie Besant. She was meditating sitting on a skin of the tiger. She was wearing pure white dress. He could recognize the photograph of Jesus also. There were many other photos around. He keenly observed every photograph. One of the photographs attracted him very much unknowingly. He continued to look at him for some time.

Krishna was very much fascinated by that peculiar portrait and his eyes transfixed on it. All of a sudden his thought sphere radiated in myriad directions. His mental bearings were cut loose and spread.

He developed a strong flood-like impetus beyond his control. The portrait was very charming, sublime, noble and seraphic in its appearance, representing the ancient wisdom embedded with spiritual secrets.

The portrait was highly magnetized; some vibrations were emanating by whirling and swirling. A feeling of flailing. Krishna experienced the vibrations like circle of waves. The influence was akin to a keyboard under the fingers of a musician.

He blinkered his eyes several times, as if he was watching a mystical element of ethereal nature, to make sure he was in his senses.

He was staring, without blinking his eyes, motionless, devoid of thought. The stillness of the room accounted for the intent void. His senses seemed to open to dizzying heights. He was powerless to move. His immobility and fixity of his gaze had a freezing effect. However he felt an unknown, yet familiar, warmth pervading in the atmosphere.

He lost all awareness of his surroundings. Though the room was small, it seemed to appear as vast and without walls. There was no sense of time and space. It was timeless! Everything stood still!

Krishna felt he was not gazing at the object of his study, but the animated portrait is, itself, watching him enticingly. That moment was irresistible. By a divine afflatus, the borders of consciousness, awakened, by the unknown thrill, which he had never felt before. Some inner voice seemed to be heard, in an extremely low tone. He felt some doors of the innards of his mind were being opened.

The portrait seemed to say, 'I was here, exclusively for you, to be discovered. Now you cannot escape from my looks; you had a goal of whose nature you are not yet aware, but which you must discover. The new task was designed by destiny, in the infinite mystery of the divine purpose.'

Was there any underlying bondage or invisible binding factor between Krishna and the portrait?

After a while the void in the entire room filled. He became conscious of his identity. The mystical moments came to an end. Krishna rose from the very depths of being into his normal self. He was released from the 'hypnotic thralldom.' Slowly he locked the room as usual and stepped down, gingerly, as if he were emerging to the earth, from the unknown realm. He walked down like a robot.

Was it a hallucination? A mental illusion? Was it an imaginary delusion of thought which decoyed him? What is thought?

All his earlier mental condition disappeared and he became totally normal. For the whole day, Krishna was thinking of that great person. He could know the secrecy of his grandfather's prayer room to some extent. But he was faced with another question—who was this great man?

Just as a honeybee enters a flower garden umpteen times, Krishna opened that room, secretly, the next day and spent some time there.

One day, he was browsing through the periodical Theosophist of the Society and suddenly he came across the history of the great saints of the Theosophical Society. There were a number of photographs in the periodical also. Among them, he could immediately recognize that great saint's photograph.

He read that some saints of Tibet continue to live forever in an invisible form and move about in the world. They appear to the competent practitioners of yoga and give initiation also. Thus, they help them to achieve spiritual progress; Krishna read about them and their greatness.

Master Koot Hoomi is one of the saints of such a series of masters. He is also called Kutubananda Swami. Krishna learnt that he is called as 'K. H.' popularly by the Theosophists. Now he was convinced that he had seen the photograph of Koot Hoomi in the prayer room of his grandfather. Krishna was thrilled whenever he thought of him. He was also convinced that someday or the other, the help of these saints would be forthcoming in his spiritual practice. He began to read the publications of the Theosophical Society.

In his own prayer room, sitting in Padmasana posture, he was meditating with deep concentration. The external noise could not disturb him. Nothing would distract his attention. When once he sat for meditation, perfect in its cadence, he would forget the entire external world. He remembered the Vedic recitals of his earlier childhood, and they were reverberating in his ears now and then. Those recitals might be remaining in his dormant consciousness. Krishna was thinking that the highest knowledge was self-realization. For a person who realized the self, nothing would be impossible. So, Krishna used to think that he should attain immortality through self-realization.

A number of gypsies, ascetics, Muslim fakirs, etc., used to come to Gudivada and stay outside the town in some forsaken places or ruined Buddharams and temples. They would wear different types of dresses. They would not stay for more than two days at any place. They are called philosophical gypsies. For the villagers, it was a practice to give alms to them as they like. If, however, anybody frowned at them, they would keep quiet and move forward. Some people would ask them for amulets for their children. It was believed that these gypsies had some invisible powers. They were giving herbs and powders for treating diseases. Late in the evening, some of them would go about in the villages singing philosophical rhythms. One of the songs conveys that the body is a leather bag with nine holes and that it may burst at any time and one has to be beware of it.

Krishna used to listen to such simple songs carefully and he was trying to understand them. He even verified the statement about the nine holes for his body. These simple philosophical songs were aimed at salvation.

Some of the mendicants were adept at rendering recondite philosophical lyrics in a simple rustic manner with the help of a tambura (a single string musical instrument) in their hands to provide the requisite music.

* * *

The house of Pantulu was always busy with visitors, relatives, dependents and others. One distant relative used to come and stay there for many days. She was a devotee, bearing sacred ash across her forehead. She could sing philosophical songs with her sweet voice well. Moreover, she was a good storyteller. She was therefore called 'Stories Kameswaramma.'

One day, Krishna observed her hiding something and entering her room. Though he observed her keenly, he pretended that he did not notice anything. Krishna observed through a hole of a door what she was doing. She opened her trunk box, kept the article in the box and locked it. She pulled the lock testing its security and went away.

Immediately, Krishna opened the box with his own key and examined the contents of the box. She was a thief. She collected a number of spoons, dishes and eatables here and there and locked them in the box.

The stories—Kameswaramma was preaching philosophy in an attractive manner. But what was she doing actually? There was no nexus between what she preached and what she practiced? Why?

Some other unknown woman, whom he did not see earlier, came to Pantulu's house and stayed for a number of days. She, too, was a devotee. She was singing the great philosophical songs of 'Veera Brahmam' and explaining their meaning analytically to the ladies. It was said that her husband could not get along with her and went away to the Himalayas. One day, while coming from outside, near the door, she noticed a one-rupee coin lying at the gate. She very quickly picked it up and hid it. Krishna observed what she did.

Later he was totally indifferent towards her like a deaf person. She told Durgamma, 'Durga! Ever since I came here, I have been observing the boy. He does not respect elders. How is it?' Durgamma replied, 'Yes, his mother left him in our hands to bring him up very carefully. He always does what he likes.'

That woman replied, 'Do you know what he did recently? When I was not at home, he opened my box and checked the contents. I asked him, 'What are you searching for?'

He replied, 'It's my will and pleasure.'

'What a headstrong reply!'

At the time of leaving the house, she asked Pantulu for some loan. He replied, 'Loan? We have no objection if you stay here for three or four days. It's not proper to ask for a loan. I know about your debts elsewhere. You are not poor. Why do you go about from door to door like this, without staying at home happily?'

Whether she was in need of money or not, she was taking loans from her acquaintances. But she would not return the money. She was not a poor woman. She had some property also. It was not known what she was doing with that money. Her thirst for money and her stooping nature could not be understood by anybody.

Some children of his relatives came to Pantulu's house once from Machilipatnam. One girl was called 'Machilipatnam girl,' specially. One day, all of them were playing and there was a little quarrel between themselves. The Machilipatnam girl slapped another girl, catching her hair and bending her down indecently. The girl could not tolerate the beatings and revolted. She caught hold of the hair of Machilipatnam girl and pulled it this way and that, in jerks. At that moment, Durgamma came that way and observed the assault on the Machilipatnam girl. She supported that girl and rebuked and punished the other girl. 'You eat freely in my house, and you beat, on the other hand, our own children. How I wish that your hands are paralyzed, you haughty girl!'

The girl continued to weep aloud and Krishna observed what all had happened. He immediately shouted at Durgamma, 'Granny, the Machilipatnam girl is at fault. She manhandled that little girl first; unable to tolerate the beatings, she revolted. You have unnecessarily punished the little girl.'

Durgamma did not care for his words. On the other hand, she called for the girl's mother and complained to her against her child. 'See, what your daughter did? Control your daughter.' The mother of the girl took away her weeping child with her, beating indiscriminately. After they left the compound, Durgamma questioned Krishna, 'What is this? You are supporting an outside girl.'